1 June 2015 | Five young men are cutting their way through dense rainforest in the northernmost part of Colombia, each wearing a sweat-drenched t-shirt colorfully emblazoned with the word “COCOMASUR” – an acronym distilled from “Consejo Comunitario de Comunidades Negras de la Cuenca del Río Tolo y Zona Costera Sur, which means “Council of the Black Communities of the Tolo River and Southern Coast” in Spanish.

At the head of the line is Frazier Guisao, a young Afro-Colombian whose ancestors settled along the Tolo River after the abolition of slavery in 1851. His brother Eusebio follows a few steps behind, along with three other community members – all of whom spent their youths in exile after fleeing in the late 1990s, when mercenaries hired by rich land owners ruled the region through torture and murder.

Today, police and army soldiers patrol both the streets and the countryside, but former mercenaries still live in town. Yet the Tolo River crew is not afraid to perform the forest patrols. They go for their daily perimeter checks, armed only with cameras and GPS-enabled cell phones, looking for evidence of illegal logging. When they find what they’re looking for – a recently-cleared patch of forest, or logging tracks – Ferney Caicedo photographs it and records the coordinates. The slender 21-year-old recently completed a professional forestry course, and aims to make this his life’s work.

“This wood is worth around three million pesos ($1,500 USD),” says Frazier, gesturing toward a smaller tree in front of him and applying the knowledge he learned when he first came home – when he was forced to earn his living chopping the forest he now protects.

All of these men could easily make more money as loggers, but they’ve chosen to protect the forest instead – a choice made possible by the Chocí³-Darién Forest Conservation Project, a trailblazing REDD project that began coalescing in 2005, when community leader Aureliano Cí³rdoba took advantage of a critical provision in the 1991 Constitution that allowed indigenous and Afro-Colombian forest communities to claim their ancestral lands. By securing collective title to the land for his people, Cí³rdoba was able to begin rekindling the attachment to the forest that many of his people lost while in exile.

“I used to be afraid,” says Cí³rdoba. “But no more. I have 1,500 people behind me now. If something happened to me, the entire community would stand to defend me.”

“Our only defense is that we are organized and determined enough to seek our rights,” says Eusebio.

The Downside of the Peace Dividend

With civil war hostilities waning and his people in clear possession of title to their land, Cí³rdoba began to look for ways to create jobs as his community recovered. He initially explored logging, but soon found that his people weren’t the only ones flooding into the territory after the danger subsided – outside loggers were coming for trees, and cattlemen along the perimeter were quietly expanding their ranches illegally.

Instead of just harvesting the forest, Cí³rdoba realized, he should be saving it if his people were going to maintain their quality of life – but how? His own people needed to make a living, and many were either logging or working on cattle ranches, which were owned by wealthy and well-connected businessmen.

To address the challenge, he developed – and won support for – a long-term sustainability strategy that would help his own people meet their needs by harvesting non-timber forest products and working at peripheral ranchers, but he also needed to keep the outside ranchers and loggers at bay.

The Genesis of REDD

In 2008, Cí³rdoba met an anthropologist from Stanford University named Brodie Ferguson, who was studying the civil war’s impact on indigenous people and Afro-Colombian communities. Both Cí³rdoba and Ferguson had heard about REDD, which at the time functioned only in voluntary carbon markets but was gaining traction in global climate talks as something to be used on a wider scale. Ferguson had asked members of the indigenous Arhuaco for their opinion, and got a surprising answer.

“Do we want to be paying the youth of our community to conserve the forest?” asked Danilo Villafaí±e, an Arhuaco chief. “Shouldn’t they be doing this anyway out of appreciation for the forest and the community traditions … just because it’s the right thing to do?”

It was a question that went to the heart of Ferguson’s PhD research, which showed that forest people, whether indigenous or immigrant, don’t want to chop the forest beyond what they needed to survive – but in the face of displacement and armed struggle, they often find themselves losing their connection to the forest. At the same time, for many of them, paying people to conserve is akin to buying a child’s affection: it turns a profoundly spiritual experience into a financial transaction.

The Economics of REDD

But Ferguson had looked into the economics of REDD, and he knew that income from selling carbon offsets couldn’t compare to any of the alternative ways to use their land: cattle ranching, cacao plantations, and gold mines. A recent study estimated that only a price above around $30 USD per ton of carbon dioxide could make a forest more valuable standing than cleared, and even then, only in some circumstances. From Ferguson’s perspective, REDD wasn’t an incentive to save forests; it was an enabling mechanism that, when done right, could bring in enough money to jump-start new activities that could take the pressure off the forest for the long term.

“It should be spent on things like education, creating environmental awareness, improving healthcare, empowering women,” he says. “Even if 100 percent of the profits go to the community – the best- case scenario – if they are not spent the right way, we are not achieving what we should be.”

Cí³rdoba realized that, in Ferguson, he had a kindred spirit.

“We don’t want the money so we can get rich,” Cí³rdoba says. “We want to develop organizationally. That way we can protect our territory, maintain peace, and improve our lives.”

Illegal Deforestation and the Myth of the Carbon Cowboy

Both men had heard horror stories of ruthless “carbon cowboys” scouring the planet in search of forests to commandeer, but most of those stories revolved around one man: a serial swindler named David Nilsson, who tried to con indigenous people in Peru by masquerading as a project developer. Most of the indigenous people he targeted, however, wouldn’t sign with him; and the contracts he did sign were declared invalid. He was roundly ignored by everyone who knew anything about conservation-based climate solutions, and he’s been rightly barred from ever entering Peru again, according to media reports.

But the mythic hordes of speculators decending on the region to gobble up forest for their carbon content turned out to be just that: myths, and for a variety of reasons.

Men from a nearby town transporting locally logged timber for construction. (Photograph: Tanya Dimitrova).

To begin with, there were the lessons of early pilot programs, which underlined the importance of involving indigenous people in a successful REDD program. Then there were the emerging carbon standards, which required the “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent” (pronounced “F-Pic”) of indigenous people before a program could proceed. And, finally, there were the economics: anyone ruthless enough to commandeer a forest wouldn’t settle for the little bit of money he could earn by saving it; he’d chop it up – as, in fact, loggers and cattlemen were already doing across the Amazon – in part because it was so cheap and easy to do so.

In countries where land is expensive and property rights are enforced, ranchers keep cows in relatively small spaces and feed them “silage” – fermented fodder produced from grass and maize – which lets them raise up to three animals per hectare, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization.

But in Colombia, ranchers average just one cow per hectare of land. That means the cows always have waist-high grass on which to graze, but only because ranchers illegally clear and fence off small plots near the edge of the forest. Global demand for commodities like palm oil, soybeans, and cattle is driving deforestation all around the world – and nearly half of that deforestation is illegal, according to a 2014 Forest Trends report called Consumer Goods and Deforestation: An Analysis of the Extent and Nature of Illegality in Forest Conversion for Agriculture and Timber Plantations.

Cí³rdoba was leery of antagonizing the cattlemen who provided jobs for so many of his people, but he also knew the ranchers could easily double their production without gobbling up more forest. He ultimately concluded that the ranchers needed workers as much as the workers needed ranchers.

REDD, he concluded, could provide a bulwark against illegal deforestation by providing money for forest patrols, with any profit going into a general fund for education and health care.

The two men then agreed to build a REDD project together.

Carbon Standards

First, they had to decide which carbon standard they wanted to use. Standards dictate everything from how you measure the carbon captured in trees to how you determine which parts of the forest are truly in danger to how you treat the people living there.

They chose the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), which was then called the Voluntary Carbon Standard, and the CCB Standard, intended for carbon projects with exceptional benefits for wildlife and communities.

To get the ball rolling, Ferguson sold his condo and created a company called Anthrotect to act as project developer.

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

FPIC requires disclosure, discussion and agreement – a process involving far more than just a few meetings between community leaders and a project developer.

FPIC means that project developers must offer information to the community, ensure they understand it through a feedback loop, allow them time for private discussions, hold meetings to answer questions, and organize focus groups to gather women’s or youth’s perspectives. It is an expensive process, involving sociologists or anthropologists, and it can take years.

Although new research from the World Resources Institute and the Rights and Resources Initiative indicates that REDD programs tend to strengthen the rights of forest people, that is not a foregone conclusion, and many forest peoples lack the legal protection that the Tolo River community enjoys. In many other countries, forest dwellers do not own the land or the forest they have lived in for centuries.

Jorge Vergara milking a cow with the help of a local boy. (Photograph: Tanya Dimitrova).

From the beginning, Cí³rdoba aimed to exceed even the stringent requirements of FPIC and to involve the whole community in the design of the project — an approach that he believed would ultimately strengthen the project by making it more attuned to the needs and desires of his people, and therefore more likely to succeed. In that spirit, he put his neice, Everildys Cí³rdoba, in charge of explaining the process to the community.

“I had to take a complex subject and try to make it simple,” she says. With the remainder of the community now on board, the Tolo River people turned their attention to measuring the carbon stored in their forests.

Measuring the Carbon Content

Ferguson sold his condo and borrowed money to bring in outside consultants like biometrician Kyle Holland of Ecopartners LLC and ílvaro Cogollo from the Medellin Botanical Garden, whose team spent three months in the Tolo River community forest studying the biodiversity and carbon it contains. They selected random plots, identified the tree species within them, and then measured their height and circumference. Using allometric equations, they calculated that one acre of the communal rainforest could contain up to 300 tons of carbon – multiples of the average carbon content in one acre of an Amazonian forest.

Since much of a forest’s carbon is found in the leaf litter and soil, the team also took soil samples and analyzed their carbon content. The samples had to be shipped to the United States, because there were no laboratories in Colombia equipped to carry out the analysis. The team then repeated the process for trees and soil in cattle pastures in order to know how exactly much carbon is left in the landscape after ranchers clear forests for pasture.

The Reference Level

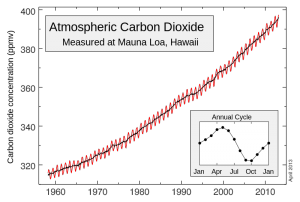

After estimating the carbon stocks in the forest, the team had to ascertain how much carbon would be released if business continued as it was going. First, they looked at the trend in historical rates of deforestation to see how much of their forest would likely be chopped down for pasture if business continued as usual. Then, using satellite imagery, they compared the forest with other unguarded forested areas nearby and concluded about 170 hectares per year (5,000 hectares total) would be lost to cattle ranching, agriculture, and selective logging if defensive actions weren’t taken immediately.

Referring back to the species composition of the forest and the trees’ average height and width, they team pegged the total greenhouse gas emissions from encroachment by ranchers at 2,800,000 tons of carbon dioxide over the next 30 years. This is equal to about 90,000 tons of carbon emissions per year.

The data collection and the analysis took the better part of 2011, and then they wrote up their analysis in a Project Description (PD) and submitted it to the VCS for a rigorous process of peer-review known as “validation” – the phase in which the VCS determines if a project’s design is, in fact, valid.

If they passed that, they’d have to then go through a process of verification – meaning they had to show they were actually taking the steps outlined in their project’s plan.

Verifying the Results

In July 2012, Pablo Reed, an independent third-party auditor, came to the Tolo River community forest to verify the carbon offsets. Reed was working for the international certification firm Det Norske Veritas (DNV), and had special experience in land-use carbon projects such as REDD+.

Reed recalls that just getting to the GPS-marked forest plots in the Tolo River community was an adventure, involving a charter flight, a boat ride, a motorcycle, a horseback ride — and then finally a trek on foot into the forest following the patrol. Reed observed Caicedo and other trained community members perform the tree measurements and then compared the numbers to what they had measured in the initial inventory.

After a reviewing the project’s documents and visiting the site, Reed and his team concluded that the forest patrols and other project actions had saved more than 500 hectares of at-risk forest. Had the forest been cleared for pasture, it would have released more than 100,000 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, or the equivalent of 20,000 cars.

Finally, in December 2012, the Verified Carbon Standard authorized the issuance of 104,000 verified emissions reductions (VERs) for listing in the Markit Environmental Registry, which is a global database of carbon projects created to ensure that offsets aren’t counted twice.

Plans for the Money

Revenue from the first tranche of credits was used to cover the cost of setting up the project as well as administrative and operating expenses like the forest patrols.

As in most community projects, the Tolo River People do not receive individual cash payments from the sale of carbon credits. “Giving out money to not cut the forest makes people lazy,” says Frazier Guisao.

Instead, they plan to use future revenue to improve the community healthcare services, send young people to universities, and strengthen the community organization, with some kept in reserve for emergencies. Beyond that, the proposals are endless.

One recent day after a morning patrol through the forest, the crew relaxed under the shade of a sun shelter that Guisao built from palm trees, waiting for the afternoon heat to pass.

“We should fix up the village school and offer professional courses for adults,” suggested one member.

“We should build an aqueduct to pipe down clean water from the hills to the village,” another offered.

Some want to use the money to subsidize struggling farmers, while others want to improve the dirt road to the village, and still others want a cell phone tower to enhance phone service in this remote region. One person mentions start-up funds for a food-delivery service by a women’s collective. Another dreams about building a community center.

In any case, as has been true throughout this particular project’s journey, the entire community is involved in how any profits will be spent.

When Deforestation Moves Down the Street

Isolated REDD projects have been used to rescue endangered patches of forest around the world, but often the loggers and cattlemen who are denied access in one location simply move down the road – an activity that carbon accountants call “leakage.” Project developers do account for it, and in theory they subtract the leakage from their total offsets, but the only way to eliminate leakage is to spread carbon accounting and control across entire states or countries.

“That’s how it was always supposed to be,” says Dan Nepstad, Executive Director and Senior Scientist at the Earth Innovation Institute. “No one ever wanted all these scattered, isolated projects dotting the forest, and even in the 1990s, it was a given that we needed jurisdictional programs to have a real impact.”

Many indigenous REDD programs are, in fact, built on a jurisdictional model – but more importantly, they are also built on an indigenous model. Like the people of Tolo River, indigenous people across the Amazon have been developing formal plans for their forest. Just as REDD was a means to an end – rather than an end in itself – for the Tolo River people, so is it for indigenous people across the Amazon. Most have spent decades developing long-term development plans called “Life Plans”, and most are finding them difficult to get off the ground. Is REDD the answer?

Tanya Dimitrova holds a masters degree in energy and resources from University of California, Berkeley. She lives in Texas and works as a freelance science and environmental journalist.

For Further Reading

This story has been adapted and condensed from a four-part series by Tanya Dimitrova. You can view the full series here:

Part One: How The Tolo River People Of Colombia Harnessed Carbon Finance To Save Their Rainforest provides an overview of the project.

Part Two: The Forest, The Farms, And The Finance: Why The Tolo River People Turned To Carbon Finance examines the drivers of deforestation in and around the Tolo River Community.

Part Three: The Tolo River Community Project: The Importance of Inclusion follows the development of the project itself – its conception, its implementation, and its challenges.

Part Four: Getting Down To Business: The Tolo River People Shift From Building Their Carbon Project To Selling The Offsets tells the surprisingly challenging story of finding and cultivating offset buyers.