Looking Back: Two Decades Tracking the Carbon Market

An abridged version of this piece first appeared in Forest Trends’ 25-year anniversary Impact Report.

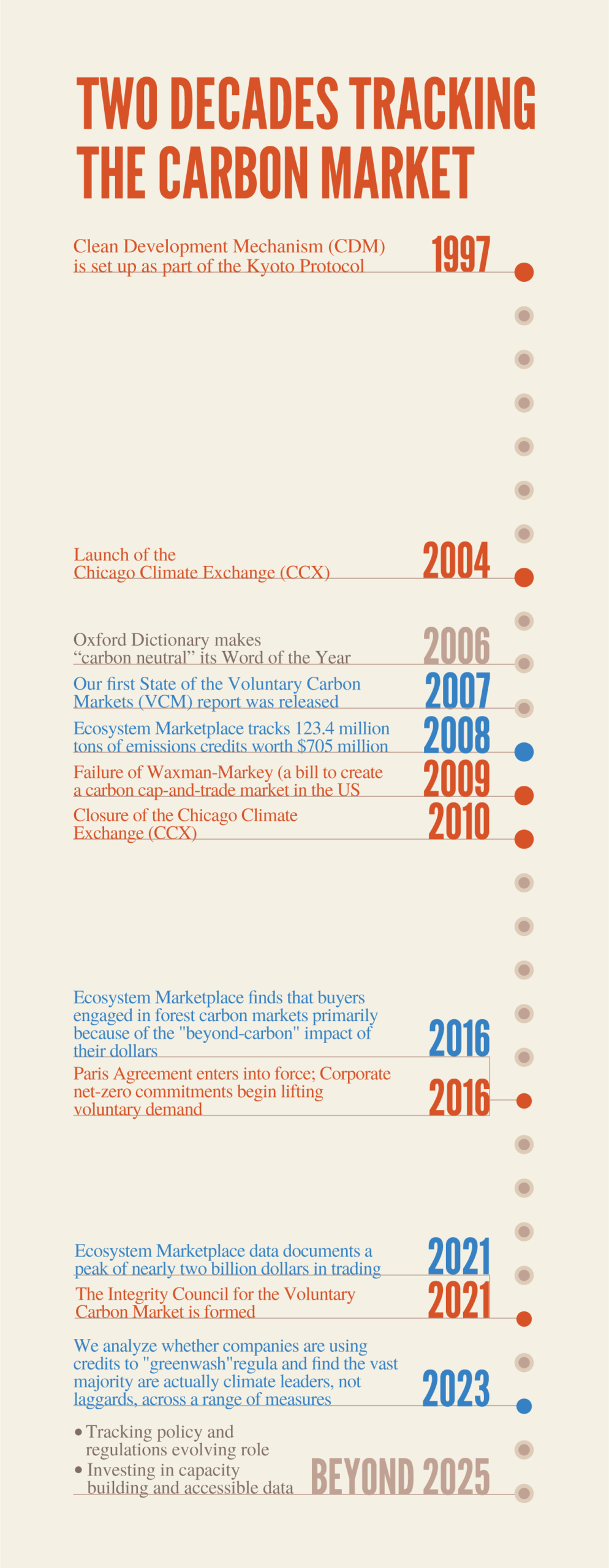

When Forest Trends started tracking the voluntary carbon market (VCM) in the mid-2000s, the landscape had already been shaped by nearly two decades of experimentation. Conservation organizations pioneered carbon finance in the late 1980s, years before any global government action on climate change. That happened in 1997 as part of the Kyoto Protocol, when the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was set up. The CDM was a market-based arrangement inspired partly by those early carbon deals and also by the success of sulfur dioxide trading under the Acid Rain Program in the US. Developed countries could invest in emissions reduction projects in developing countries and get carbon credits that counted toward their own targets.

The CDM didn’t kick in fully until 2005. Voluntary carbon markets were the only game in town for a long time. The arrival of the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) in 2004 was a milestone, creating the first voluntary, membership-based cap-and-trade system and bringing more structure to what had been a fragmented, bilateral market.

The CDM didn’t kick in fully until 2005. Voluntary carbon markets were the only game in town for a long time. The arrival of the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) in 2004 was a milestone, creating the first voluntary, membership-based cap-and-trade system and bringing more structure to what had been a fragmented, bilateral market.

Our first State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets report was released in 2007, offering reliable data on how any of this actually worked. For two decades now, we’ve been trying to shine a light on how the voluntary carbon market has evolved—not as passive observers but using transparency and analysis to help the market find its footing, navigate crises, and mature into something more sophisticated than it started out as.

Part I: The Wild West

The early VCM was, as we put it in 2007, “the wild, innovative, inventive, and often misunderstood family rebel” of climate finance. It was also tiny.

“Compared to the regulated markets, the CCX and over-the-counter markets together traded [last year] an amount equal to roughly 2% of the volume of the EU Emissions Trading Scheme market, or about what the EU ETS currently transacts in a week,” our analysts noted.

But the VCM was growing fast. Dell, Google, Nike, Delta were all making big offset purchases. Climate change was moving closer to the mainstream of public consciousness. In 2006, the Oxford Dictionary made “carbon neutral” its Word of the Year. Media coverage got increasingly critical, with questions raised about offset quality, additionality, and whether purchases represented genuine climate action or merely “feel-good hype.”

The market’s response was to show it could self-govern. Third party standards multiplied. By 2008, when we tracked 123.4 million tons of emissions credits worth $705 million, we also noted that 96% of credits were now verified by third parties.

Our State of surveys from those years show that corporate social responsibility and a desire to “walk the talk in terms of environmental stewardship” were the main motivations for purchases. That tracked with the language of the CDM, which specifically mandated any projects developed under its framework must lead to sustainable development in the host country.

The VCM was expected to go one better than the rule-bound CDM, being the instrument “most likely to reach poorer and smaller communities in developing countries…[and] lacking the bureaucracy and transaction costs of their regulated counterparts.”

Voluntary carbon markets, in other words, were described as a dynamic new tool to funnel private finance toward a green economic transformation. Yet there was also a second purpose for getting involved in the voluntary market: Companies expected regulated markets to come online at some point, and the voluntary market was framed as a kind of sandbox where credit suppliers could test methodologies and buyers could get experience sourcing credits. In this view of things, the point of a carbon market was essentially to enable offsetting, and the challenge was to demonstrate high-enough standards that companies could “stand behind” their credit purchasing.

If there was a tension between the need to project that kind of stringency and the VCM’s role as an experimental channel for sustainable development finance, in the early years it never reached a breaking point.

Then came the Great Financial Crisis, the 2009 failure of Waxman-Markey, and the 2010 closure of the CCX. The voluntary carbon market staggered. Any idea that companies should prepare for imminent carbon regulation got kicked into the long grass.

Part II: The Lean Years

The VCM subsisted on dribs and drabs of corporate social responsibility purchasing for years. Through those lean years, our work took on different importance. We weren’t just documenting transaction volumes; we were investigating what the market was actually delivering.

One critical finding from our 2016 survey of forest carbon projects showed that over half of project developers said their buyers engaged in forest carbon markets primarily because of the “beyond-carbon” impact of their dollars. At least 10.7 million tonnes of emission reductions found a buyer in large part because of co-benefits like biodiversity protection, community land tenure, jobs, and training. Buyers clearly valued more than just tonnage, but it’s important to note that in those years they weren’t yet paying big premiums for verified co-benefits.

Perhaps more importantly, by bridging our transaction data with corporate climate disclosures, we showed (in 2016, and again in 2023) that companies purchasing carbon credits were consistently more likely to be leaders across the board on climate metrics. That directly challenged the narrative that offsetting was evidence of greenwashing rather than a signal of genuine climate commitment.

These insights helped sustain the market’s legitimacy through some pretty difficult years. When the Paris Agreement entered into force in 2016 and corporate net-zero commitments began lifting demand, there was groundwork to build on. The market experienced explosive growth in a short period of time: our 2021 data documented a peak of nearly two billion dollars in trading.

Part III: The Big Time

Then came a second round of bad press. High-profile investigative journalism questioned, over and over, the integrity of forest carbon projects. In response, the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market was formed, as was the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative. Standards updated their methodologies. Ratings agencies emerged. New remote sensing technology, machine learning/AI processing, and blockchain were touted as breakthrough solutions. Market actors embarked on deeply technical and highly public discussions over tricky issues like additionality, permanence versus durability, the proper ratio of removals versus reductions credits in a portfolio, and so on. Ironically, these iterative improvements and mostly good-faith debates got interpreted by some carbon market critics as just more evidence of the VCM’s fundamental failures.

Through all of this, our data revealed something crucial: the market was bifurcating. Demand began splitting between buyers seeking permanence (technological solutions like direct air capture, biochar) and those seeking highly differentiated, relationship-driven, multiple-benefits projects (many nature-based solutions). Both groups are willing to pay premiums for “high quality,” but “quality” means fundamentally different things to them. The old tension—is the VCM for bulletproof carbon accounting or for funneling finance to sustainable development?—was showing up in new forms.

Our analysis suggests we may see further bifurcation. Engineered removals and nature-based solutions are unlikely to ever trade at the same price or meet identical standards. Perhaps we’re seeing a “commodity tier” emerge (fungible, liquid, boring) alongside a “specialty tier” (differentiated, premium, relationship-driven). Think about how the specialty coffee market evolved: beyond commodity pricing through layering of certifications or scorecard ratings tailored to different buyers, and storytelling around provenance and origin.

Throughout this period, we’ve kept up our work explaining big picture shifts to the “carbon curious” while tracking critical policy intersections like Article 6 implementation. Our continued investment in non-paywalled data has been deliberate. The actors who need our insights most—project developers navigating increasingly complex diligence requirements, communities engaging sophisticated buyers, suppliers making determinations about technology transitions and new methodologies—are often the ones least able to pay for it.

The Road Ahead

The Road Ahead

After two decades, we’re pretty clear-eyed about what the VCM is and isn’t. That world where cap-and-trade would eventually regulate emissions globally? It hasn’t materialized, at least not on the timeline anyone expected. But regulation hasn’t disappeared either. It’s simply evolved more slowly and unevenly than predicted, creating a complex patchwork that projects and buyers have to navigate.

Meanwhile, the bifurcated market we’ve been documenting is an intriguing maturation. But it requires new kinds of support. Projects are feeling squeezed by multiple rounds of diligence from buyers, investors, standards, and ratings agencies. Consultants seem to be capturing an awful lot of value in the middle, in ways that remain opaque despite much-vaunted improvements in transparency. The shift toward forward offtake agreements, while providing much-needed demand certainty, and in some cases upfront finance, has the potential to concentrate power among relatively few high-volume corporate buyers.

This landscape clarifies our priorities for the next phase:

- Tracking policy and regulation’s evolving role. As Article 6 mechanisms come online and various jurisdictions experiment with compliance markets, we’ll track how these interact with voluntary action, where they create opportunities, and where they create friction.

- Investing in capacity building and accessible data. We’re doubling down on our commitment to non-paywalled information and direct support for project developers. As market requirements grow more sophisticated, the gap between well-resourced and under-resourced actors widens. Ensuring that communities and smaller developers can navigate diligence, engage buyers on equal footing, understand technology options, and anticipate policy implications isn’t just about equity—it’s essential for the market to actually function.

- A view beyond the VCM. The voluntary carbon market was never meant to be a silver bullet. Our work examines how it functions alongside other climate and nature finance instruments—natural capital investing, supply chain insetting, results-based payments, biodiversity credits, debt instruments, and so on. Understanding these tools in tandem, rather than in isolation, is critical for directing capital where it’s needed most.

The market we track today looks nothing like the one we started documenting twenty years ago. It’s more sophisticated, more scrutinized, more stratified, and more effective. Our job remains what it’s always been: bringing transparency to complexity, using data to inform better decisions, and making sure that market evolution serves not just carbon accounting, but genuine climate action and sustainable development.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.