Voices from the Forest: In Kenya, a Carbon Project’s “Co-benefits” Take Center Stage

For most companies or people buying carbon credits, the whole point of the transaction is that ton of carbon. Co-benefits like poverty reduction and wildlife protection had been historically seen as just a nice add-on. What most buyers don’t understand is that for projects on the ground, co-benefits aren’t extras – they’re what make emissions reductions possible. Last month, I traveled to Kenya to visit the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project, to understand how this reality plays out on the ground.

29 June 2023 | KASIGAU CORRIDOR | Kenya| Catherine Simba administers 32 schools across southern Kenya, an arid farming region that’s also the home and a migratory route for elephants, giraffes, zebras, and other animals that coexist with people.

We saw these stunning animals from the windows of the train that we took from Nairobi and from the safari van as we traveled around on the maze of unmarked dirt roads that we took to meet Ms. Simba at one of her schools.

This natural spectacle was not lost on me. Having grown up near New York City, until visiting Kenya, I had only seen such animals in zoos, films, and children’s stories.

Known as the Kasigau Corridor, this region connects the Tsavo East and Tsavo West National Parks, and twenty years ago it faced both rampant deforestation and poaching, which led to the decimation of the Rhino population in the region.

Make no mistake, those threats are really symptoms of social stresses such as poverty and hunger. So when the for-profit company Wildlife Works began its conservation work here two decades ago, it aimed to protect nature by empowering people. This ultimately led to the creation of the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project.

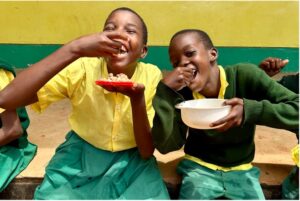

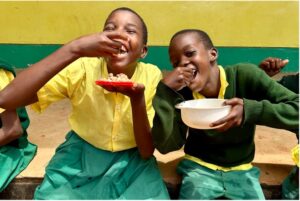

The REDD+ project finances its operations by generating carbon credits from protecting threatened forests. But for Simba, the project’s value comes in the way it impacts the thousands of squealing children she calls her “babies.”

“Before carbon, the babies weren’t coming to school,” she says, as dozens of those babies swarm to greet her outside the Marungu Primary School.

The government, she says, pays for early education, but it doesn’t cover school lunches, and it doesn’t cover high school or college.

“Carbon gave me a feeding program, so retention in school has increased,” she says. “This is often the only meal they get, and they used to pass out in school.” After the babies graduate, the carbon project will subsidize their secondary and university educations.

Hear from Catherine Simba

To buyers of carbon credits, education is a “co-benefit” or a “beyond carbon” benefit. But market actors tell Ecosystem Marketplace they’re seeing buyers increasingly willing to pay extra for projects that demonstrate verified support for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) other than SDG 13, the goal to reduce climate change.

At the same time, intermediaries say they’re still struggling to explain the value of co-benefits to end buyers – largely because most people don’t really understand how carbon projects work, and there has been little effort to overcome that education gap.

Ecosystem Marketplace visited the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project for a series of interviews with Wildlife Works staff and people from the local communities to get a feel for how these beyond carbon benefits work on the ground.

Returns from sales of carbon credits have also been used to update bathrooms that offer sanitary conditions and privacy for the children and teachers. They’ve also been used to create reusable sanitary napkins, which the school administration we spoke to say has led to greater attendance rates among the girls.

Hear from Students Riziki Paul & Salma Ibrahim

The benefits themselves are often clear, but the link to emission reductions can be elusive. From the beginning of the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ Project, for example, Wildlife Works has centered communities’ self-governance. Communities choose the development of activities focusing on an array of social, health, and economic development issues. Today the project activities positively impact the project area’s population of over 116,000 people, including the creation of 400 local jobs. It’s also ensured the protection of 20 species of bats, over 50 species of large mammals, over 300 species of birds and critical populations of IUCN Red List species such as the Grevy’s Zebra, African Elephant, lion, and African Wild Dog.

But how do these efforts protect forests – or are they just philanthropic add-ons?

To Simba, the connection is clear. She says education will reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) in the area by helping her babies grow into adults who can earn a living without poaching wildlife or burning trees to make charcoal. It is, in other words, a means to an end and not a philanthropic add-on.

Geoff Mwangi says that’s usually the case, and he argues the terminology is misleading.

“We recognize what you are calling ‘co-benefits’ as ‘core benefits,’” he says.

Mwangi is the lead scientist for biodiversity and social monitoring at Wildlife Works,’ Kasigau Corridor project and he echoes Simba’s contention that the project is reducing deforestation by reducing poverty; the two outcomes cannot be separated.

He adds, however, that it’s also harder to reduce deforestation by reducing poverty than it is to, say, encourage IFM in developing countries, and he emphasizes that SDGs don’t always lead directly to reduced emissions. Some sustainable development outcomes are byproducts, and some come at a cost to the project. For these reasons, it’s critical to ensure that SDG benefits are properly certified and supported.

Hear from Geoffrey Mwangi

EM’s carbon markets data suggests that many REDD+ projects appear to be excelling particularly when it comes to SDG 5: gender equality.

Constance Mwandaa is a case in point. She grew up in the Kasigau Corridor and became the first female Wildlife Works ranger to patrol the plains. Today, she oversees all training for the force of over 100.

For her, the REDD+ project is about female empowerment. “I have a few girls at home who see what I’m doing, and they say, ‘We can do this!” she says.

And she’s hardly alone. All across the project area, I met women whose lives the project had improved, often in ways that reduce deforestation and dependency on bushmeat.

Constance Mademu, for example, who used to engage in slash-and-burn charcoaling is now employed by Wildlife Works as a part of their sustainable charcoaling micro business built around selective, regulated harvesting and efficient burning.

I also met dozens of women who’ve enrolled in a training program to implement climate-smart agriculture that blends no-till farming with agroforestry. When speaking with them, I asked why mostly women were being trained and are the ones responsible for managing the land. Bluntly, I was told it was because the men were either dead, gone, or inebriated – a response I wasn’t expecting but it did put into focus the social dimension in a new way.

In other areas, people had shifted from charcoaling to beekeeping and honey production. Many were making textiles, t-shirts, and handicrafts – activities made viable because of the carbon finance.

“The income I make here far surpasses what I would earn charcoaling, and it’s also less physically demanding,” said Nora Matunda, who works in a boutique soap factory that Wildlife Works finances through a blend of sales and carbon finance.

“The ultimate goal is to create a sustainable economy built on non-destructive practices such as these, and one that can outlast the carbon project itself,” says Laurian Lenjo, who oversees community outreach along with Joseph Mwakima.

“For now, we need carbon finance to support these activities,” he adds.

The two men spend the bulk of their time bouncing among six administrative districts in the project area, which is home to more than 116,000 people.

I accompanied them to several meetings where villagers were voting on how to spend their carbon payments.

Hear from Joseph Mwakima and Laurian Lenjo

“Different communities identify different needs, but the key point is they get to choose for themselves how to spend it,” says Lenjo. “The initial votes tended towards school facilities, but now we are seeing more diversity. Several villages recently voted to create a health center, because the existing facilities are so far away, while another voted to create a community meeting center.”

Suleiman Mwamanga is a village elder who guided us to a new water tank.

“We elected to build this tank as the drought intensified,” he says. “The water comes from the Chyulu Hills, which provide water across this region.”

Ten years ago, that source had run dry due to degradation in the Chyulu Hills cloud forest — degradation that was reversed by the Chyulu Hills REDD+ project, which saved the forest and revived the springs that flow from it.

In SDG parlance, that project contributed to Goal 6, clean water and sanitation.

As standards develop more and better means of quantifying and certifying SDG impacts, we can hope to see more support for these once-intangible benefits – but only if the sector learns to tell its story more effectively.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.