Shades of REDD+The Durability Dilemma: Navigating the Science and Politics of Carbon Removal

Debates over durability have fractured the carbon dioxide removal (CDR) community into opposing “nature-based” and “tech-based” CDR camps, each vying for policy recognition and financial support for their preferred approaches.

With these tensions likely to flare up again in the consultations around the non-permanence standard guiding Article 6.4 projects under the Paris Agreement, it’s worth exploring why this dichotomy is both unnecessary and counterproductive – as argued in our recent paper in the Journal of Climate Policy. While durability is a relevant aspect of CDR, it should be weighed alongside other factors such as scalability and co-benefits, and in relation to varying climate and policy objectives.

Below, we unpack the concept of durability (or ‘permanence’) and introduce a broader framework for evaluating CDR approaches: one that recognizes that nature-based and tech-based CDR methods are complementary, and that opens the door to portfolios that can deliver across short-, medium-, and long-term climate goals.

Durability: the science of CDR

CDR is a necessary component of global climate change mitigation strategies. While rapid and massive reductions in gross greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are non-negotiable, meeting the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement will also require large-scale deployment of CDR.

| Box: What is CDR?

CDR refers to human-induced processes that actively remove CO2 from the atmosphere. This can be done with a variety of methods, which are usually grouped within two main categories: nature-based (conventional) methods, which enhance natural carbon sinks through activities like forest or wetland restoration; and tech-based (novel) methods, which use techniques such as direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS) or enhanced rock weathering. |

For CDR to effectively contribute to climate goals, it must be durable, which implies a long-term sequestration of CO2 into non-atmospheric pools. However, what exactly is meant with durability is contested. Because tech-based CDR methods tend to involve more chemically stable forms of storage, they are often considered more durable than nature-based CDR methods that store carbon into biomass. As a result, tech-based CDR methods have increasingly been promoted as priority CDR mitigation investments.

Though the precise definition of durability (or, often used in carbon markets, ‘permanence’) has been contested, it generally implies that the carbon it removes is stored into non-atmospheric pools over the long-term with low risk of reversal. Durability can be understood to consist of two components:

- The required duration of storage, which depends on the specific purpose for which CDR is used (i.e., counterbalancing emissions, or slowing the rate of temperature increase)

- The risk of reversing storage, which is the probability of stored carbon of being fully or partly emitted back to the atmosphere

Applying this definition allows classifying CDR methods according to their durability in a more nuanced way. It also helps decision-makers assessing CDR methods’ suitability for more comprehensive and integrated CDR strategies, that build on the complementarity of nature-based and technology-based CDR, to deploy them in synergistic packages.

The Durability, Readiness, Social and Environmental Dimension of CDR

Reducing the decision of when and how to incentivize CDR to only a question of durability narrows the focus to a single factor, obscuring the broader complexity that decision-makers must navigate. There are multiple dimensions that policymakers need to consider when evaluating CDR:

- Climate impact – How does CDR contribute to both short-term and long-term climate goals?

- Deployment readiness and costs and benefits – Is a given CDR method ready for deployment at scale, at what cost, what are the barriers?

- Sustainability – What are synergies and tradeoffs with other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

As already elaborated in an earlier blog, while fully counterbalancing fossil CO2 emissions requires removing CO2 and storing it for millennia, shorter-term CDR has significant climate benefits: It helps achieve net GHG emission reductions in the next few decades and can slow the rate of warming reducing the risk of tipping points and severe impacts on nature and people.

With the right social and environmental safeguards, nature-based approaches offer not just carbon removal, but a host of benefits that make them key players in the path towards SDGs. Nature-based CDR that involve the restoration of natural systems, such as deforested or degraded lands, wetlands, and coastal ecosystems are key for enhancing ecosystem resilience, protecting livelihoods, and protecting biodiversity.

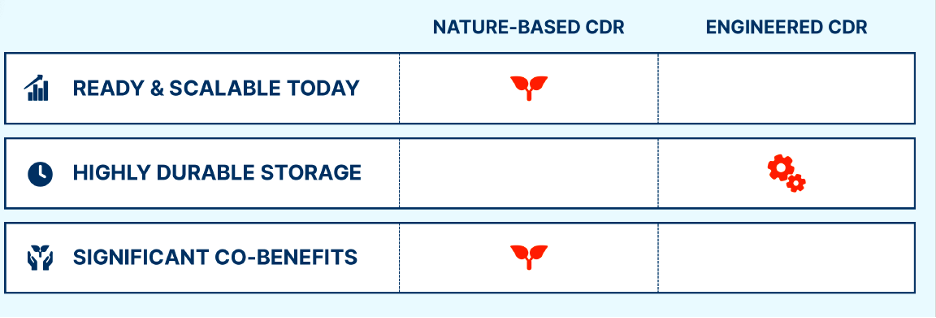

Therefore, when assessing CDR, adding criteria such as technological readiness, economic feasibility, and co-benefits for society and biodiversity alters the equation (See Figure 1. The scales begin to tip in favor of nature-based CDR solutions—not as a replacement for more durable, engineered removals, but as a vital complement.

Figure 1: The dimensions of CDR

Durability: Financing of CDR

Much of the debate over the “right kind” of CDR is less about science than about a scramble for resources. Engineered CDR – like DACCS – remains far from cost-competitive, particularly when measured against cheaper, nature-based alternatives.

In response to this imbalance, some proponents of tech-based CDR have sought to position their approaches as superior, often by downplaying or discrediting nature-based methods and seeking to create rules that create barriers for investments in nature – all in the hope of unlocking targeted financial resources for tech-based CDR.

Carbon markets have become a particularly contested arena in this debate. Instead of facilitating different type of CDR through different instruments, rules often discriminate against nature-based solutions, in particular community-led projects and programs.

Take for example, the Article 6.4 “Draft Standard Addressing non-permanence / reversal”, released for public comment on July 15. The draft allows technology-based CDR projects to claim a “negligible risk of reversal” based solely on modeling – effectively exempting them from having to monitor or account for actual reversals. This is a surprising and unearned leap of faith, especially given that many of these technologies remain largely untested at scale. The introduction of this “negligible risk” category appears not only unnecessary, but also serves to pre-emptively frame tech-based CDR as superior to nature-based solutions, despite the latter’s proven track record and broader co-benefits. Even more concerning is a new requirement that project participants must prove they are not at risk of insolvency—a criterion that could disproportionately disadvantage Indigenous Peoples, community-led initiatives, and small-scale actors who may not have access to the same financial guarantees as large corporations.

It is also interesting that despite this “negligible risk of reversal” contractually or legally, engineered CDR proponents tend not to offer liability for durability beyond a couple of decades – often less than nature-based CDR.

Durability: Integrated portfolio approaches

Urgent action on CDR is needed and there is no time for further controversy or elbowing. At this time, there is no single CDR method that has a high likelihood of securing adequate and sustainable carbon removal that is ready to be deployed, can store sufficient carbon to reduce the temperature peak, and counter-balance CO2 emission in the long-term.

As a result, what is needed are nuanced policies that mobilize finance for various CDR approaches. This includes creating demand for CDR generated by carbon markets, but also (i) direct R&D and venture support for novel, tech-based CDR methods, and (ii) rules that incentivize investments into nature, including in developing countries’ high-carbon and high-biodiversity ecosystems. These investments are essential to meet climate and biodiversity goals.

Long-term storage can also be achieved by using tech-based CDR strategies, deployed at scale in the second half of the century, to manage the reversal risks of nature-based CDR, deployed now. Deploying nature-based CDR today that is partially reversed and replaced after 2050 with tech-based CDR is also financially more attractive than suffering damages from temperature overshoot until tech-based CDR is ready to be deployed at scale after 2050. While supporting tech-based CDR readiness and feasibility, further research can help to understand trade-offs around energy, biomass and land use as well as equity implications of different CDR methods.

Currently, of the annual 2 GtCO2 removed globally, less than 0.1% comes from novel technology-based CDR methods. The remainder is achieved through nature-based CDR, such as reforestation and soil carbon enhancement, which are widely tested and scalable. Investing in nature is not optional; it is the only viable near-term path while engineered solutions mature.

Researchers, decision makers, and CDR players should shift from discussing what is and what is not durable, to focusing on supporting integrated CDR portfolios that help meet short- and long-term climate goals without further delay.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.