Este artículo apareció por primera vez en el sitio web de Peoples Forests Partnership.

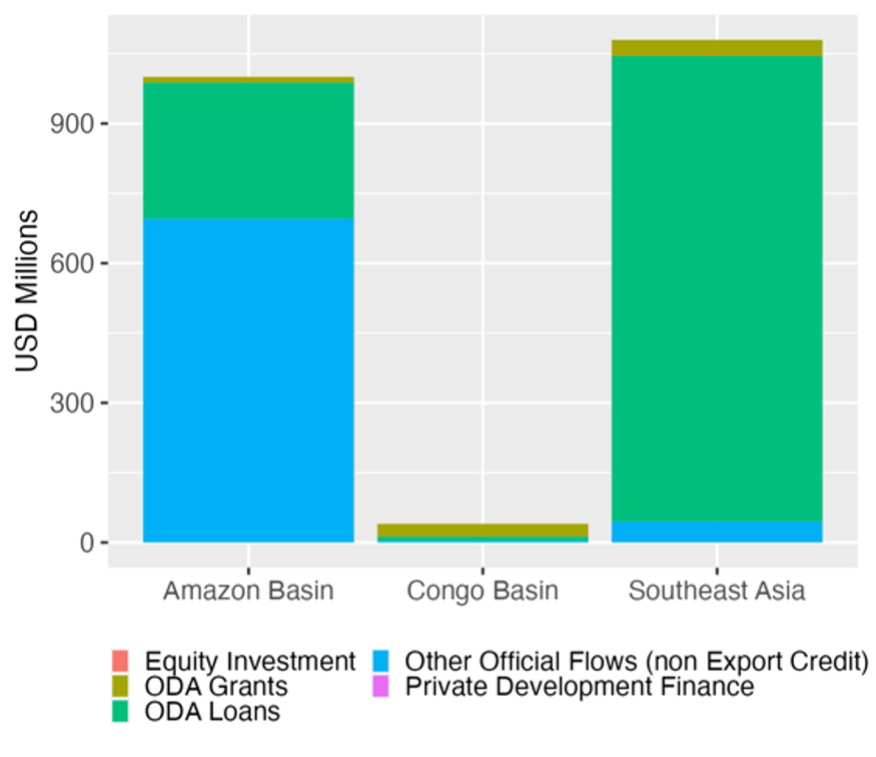

Los mercados de carbono y otras formas de financiación climática se enfrentan a una crisis de confianza y credibilidad. Existe un potencial increíble para que los programas de financiamiento climático canalicen millones de dólares directamente a los pueblos indígenas y comunidades locales (PI y CL) que administran el 36% de los bosques del mundo y el 80% de su biodiversidad. Pero cosas como los “vaqueros del carbono” mal preparados que se apresuran a emprender proyectos y causan desconfianza entre las organizaciones locales, la falta de estándares y salvaguardias, y requisitos técnicos y legales tremendamente complejos, han hecho que los actores del mercado, especialmente los PI y las CL, sean cautelosos a la hora de participar.

Establecer transparencia, integridad y confianza entre los PI y las CL y otros actores del mercado es esencial para restablecer la confianza en estas herramientas financieras críticas. Los actores del mercado exigen mejores recursos y apoyo técnico para participar eficazmente en los mercados de carbono. En respuesta a este llamado, se lanzó la Peoples Forests Partnership (PFP) en la COP26 en Glasgow para ayudar a conectar a los PI y las CL con oportunidades de financiamiento directo y hacer que la participación en estas oportunidades sea más accesible, transparente y equitativo.

Un modelo singular para la construcción de conocimiento.

Con tanto claramente en juego para los bosques de nuestro mundo y las comunidades que los salvaguardan, la PFP reunió a sus miembros en América Latina del 18 al 20 de marzo para una reunión regional cerca de la ciudad de Tena en la Amazonía ecuatoriana. El objetivo de estos tres días fue hacer un balance del estado actual de los mercados de carbono, la evolución de la oferta y la demanda, la reforma de las normas y otras formas de financiación climática, facilitar un espacio seguro para intercambiar conocimientos y experiencias, y construir una visión compartida para el trabajo futuro juntos para el PFP.

Las conversaciones abarcaron desde inteligencia de mercado hasta cuestiones técnicas de proyectos y desafíos políticos, todas ellas enmarcadas en torno a la creación de entendimientos comunes y el fomento de debates profundos sobre los desafíos enfrentados y dónde se necesita trabajar. Todas las discusiones se llevaron a cabo bajo la Regla de Chatham House, lo que significa que la información se puede compartir fuera de la reunión, pero no atribuirse a una persona u organización específica. Estos parámetros fomentaron puntos de vista y debates más diversos y apoyaron la creación de confianza entre los participantes.

“La creación de relaciones basadas en la confianza y la rendición de cuentas es parte de lo que hace que la PFP sea una iniciativa tan valiosa y oportuna; y del que nuestra empresa se enorgullece de formar parte”, destacó Blanca Bernal, de Green Collar, tras el evento.

La diversidad de asistentes y la profundidad del compromiso durante la clínica envían un fuerte mensaje de compromiso y colaboración y es un reflejo del momento oportuno para este diálogo. Los participantes identificaron riesgos y precedentes negativos, así como el potencial de los mecanismos de financiamiento climático para apoyar los Planes de Vida indígenas, la gobernanza territorial y las economías indígenas, basados en la participación informada y la igualdad de condiciones.

La reunión fue mucho más que un simple intercambio de información; el PFP ha creado un lugar seguro singular para que los PI, las CL y las empresas aprendan sobre el financiamiento climático, compartan desafíos y éxitos y generen confianza.

“El evento en Tena fue un encuentro muy importante, donde hermanos, indígenas y no indígenas, empresas privadas y ONG, nos reunimos de buena fe para un intercambio de experiencias con diferentes criterios y perspectivas”, reflexionó Domingo Peñas, líder y dirigente Achuar. Presidente del órgano de gobierno de Cuencas Sagradas.

Aquí hay tres mensajes clave de los asistentes a la reunión sobre cómo el financiamiento climático puede funcionar para los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales:

1. La financiación equitativa de la lucha contra el cambio climático comienza con un intercambio equitativo de información.

Los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales (PI y CL) reclaman información sobre la financiación de la lucha contra el cambio climático que sea fiable, de calidad, accesible y culturalmente adecuada. La necesidad de capacitación no es un tema solo de los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales. Las empresas, los gobiernos y las ONG también piden herramientas para relacionarse mejor con los PI y CL para contribuir a resultados equitativos y eficaces fundamentados en un diálogo transparente.

Algunos de los temas clave que escuchamos durante el evento fueron la mejora de la información sobre el consentimiento libre, previo e informado (CLPI); las salvaguardias y los mecanismos de reclamación; los distintos marcos y normas reguladores; los criterios para identificar a socios creíbles; y la mecánica de los contratos y los mecanismos de distribución de beneficios.

La necesidad de capacidad e información también trasciende a los individuos. La capacidad actual de muchas organizaciones para proporcionar apoyo y orientación técnica, financiera y jurídica especializada a sus miembros se ve limitada por la falta de personal, tiempo y recursos materiales. Uno de los objetivos del PFP es apoyar la capacidad de las organizaciones locales y regionales para que estén mejor equipadas para acompañar a las comunidades locales.

2. Los IPS y LC han asegurado sus asientos en las mesas donde se establecen de reglas, y eso significa que hay mucho trabajo por hacer.

Ha habido un avance notorio para que los PI y las CL participen directamente en la configuración de las reglas que rigen los diferentes mecanismos de financiamiento climático, desde los procesos de la ONU hasta los estándares, certificaciones y otros marcos voluntarios e industriales. Se les invita cada vez más a participar en debates, pero los asuntos suelen ser especializados y extremadamente técnicos, generando nuevas demandas sobre los líderes y el personal técnico de las organizaciones que ya están al límite con diversas frentes de trabajo. A los PI y CL se les pide que representen los intereses de sus comunidades en los foros globales, al mismo tiempo que enfrentan peligros inmediatos y múltiples desafíos, incluyendo amenazas y asesinatos de los defensores ambientales.

Gustavo Sánchez, miembro de la Alianza Mesoamericana de Pueblos y Bosques (AMPB, México) subrayó la importancia del momento: “Tenemos una enorme oportunidad de incidir en cómo deben operar los mecanismos nacionales e internacionales para que beneficien y no perjudiquen a las comunidades. Esto es a la vez un gran desafío y una gran responsabilidad”

Para participar efectivamente en espacios donde se establecen las reglas, los miembros de PFP están pidiendo el fortalecimiento, dentro de las organizaciones de PI y CL, de equipos dedicados con la experiencia técnica y en políticas requerida. Esta necesidad existe tanto a nivel nacional como internacional.

3. El carbono no es la única medida del éxito.

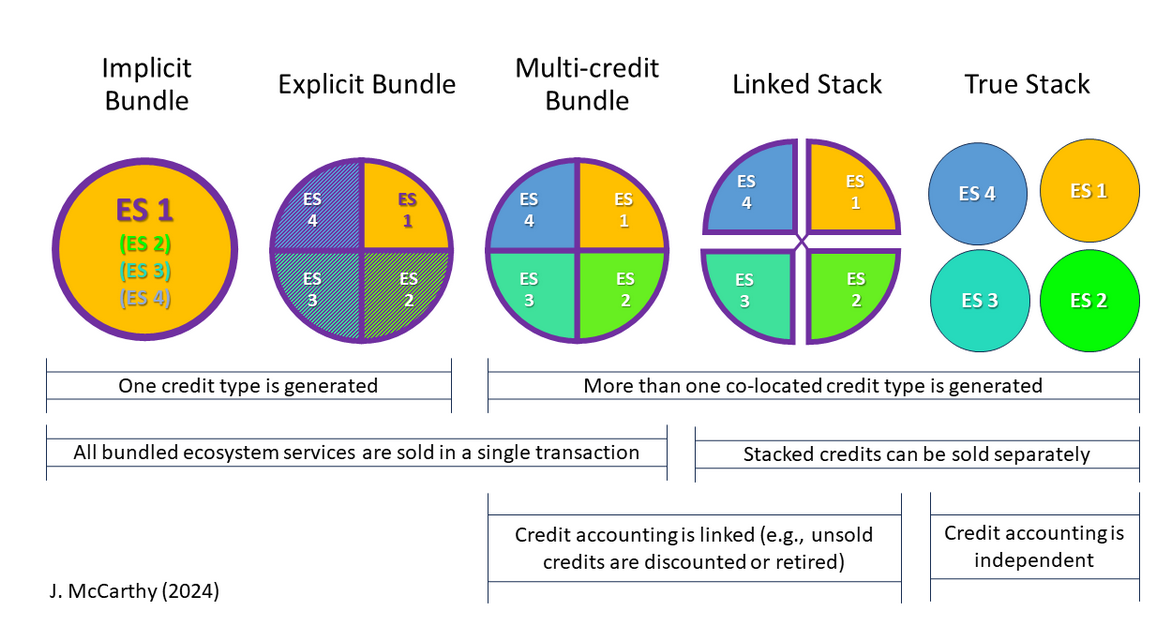

Un mensaje recurrente de los PI y las CL es que un enfoque limitado en las métricas de carbono como indicador principal del éxito del proyecto no se alinea con sus relaciones tradicionales con sus bosques y territorios. Excluye métricas más centradas en el ser humano, como derechos claros sobre la tierra y los recursos, una organización y gobernanza sólidas, y una serie de otros valores ecosistémicos, culturales y espirituales. Si bien el carbono es un variable fundamental frente a la crisis climática, los mecanismos centrados únicamente en reducir las emisiones tienden a marginar a aquellas comunidades y territorios que históricamente han demostrado una buena gestión forestal y, por lo tanto, tienen menos emisiones que reducir.

Durante el evento, vimos un gran interés en desarrollar mecanismos alternativos que compensen la buena gestión territorial, como impulsar el financiamiento hacia territorios indígenas de áreas con alta cobertura de bosques y baja deforestación (HFLD) y mecanismos emergentes que valoren la biodiversidad.

Avanzando en una agenda común del PFP en América Latina

Salimos de este tiempo juntos emocionados por una comprensión colectiva más profunda de los contextos políticos y de mercado actuales e inspirados por la voluntad de los participantes de ser abiertos unos con otros y aprender de los conocimientos de los demás. La colaboración entre participantes muy diversos afirmó el espacio singular la Peoples Forests Partnership (PFP) como un espacio seguro para debates políticamente sensibles y técnicamente complejos, así como una plataforma que puede elevar las voces de los PI y CL para compartir lecciones aprendidas y convertirse en voceros de mecanismos que les funcionan.

“Nuestros miembros nos han dado un mandato claro para construir una plataforma que fomente la colaboración radical e impulse el conocimiento y la innovación centrados en la comunidad en espacios técnicos, políticos y financieros”, dice Anna Lehmann, directora ejecutiva del Comité Ejecutivo Interino de la PFP. “Las voces de la comunidad son fundamentales para crear flujos financieros que trabajen con la red de la vida y no en contra de ella”.

La PFP espera trabajar junto con nuestros miembros para continuar este trabajo en América Latina y en todo el mundo. Esperamos continuar ampliando nuestros esfuerzos de creación de conocimiento para individuos y organizaciones, iluminando los bosques del mundo con fuertes defensores y líderes en este espacio.