Indigenous People Explore Many Shades Of REDD

Indigenous people have long been the most effective guardians of the rainforest, but confronted with growing global pressures to clear their lands, how will they find the resources needed to protect their forests and thrive? In this series, we will explore the new emerging mechanism known as “Indigenous REDD” and see how it draws on and contrasts with forest-carbon projects that exist to date.

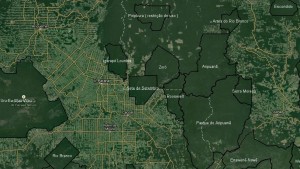

15 January 2015 | On a daily basis, logging trucks rumble up an offshoot of Brazil’s Highway 364, laden with muddy trunks illegally harvested from the Zorí³ Indigenous Territory, at the southern edge of the Amazon Rainforest, along the border between the Brazilian states of Rondí´nia and Mato Grosso.

The bounty includes old growth teak and mahogany, the crown jewels of the Amazon rainforest destined for luxury furniture showrooms across Brazil and around the world. The finished wood from a single mahogany trunk can fetch tens of thousands of dollars, and a few pennies of that will go to members of the Zorí³ indigenous people who illegally escort loggers to the most productive parts of their forest. It’s a practice in which many Zorí³ say they’d rather not engage, but they see no choice if they’re to feed their families.

After leaving the Zorí³ territory, the trucks pass along the northern edge of the Sete de Setembro, where the Paiter-Surui community once logged just as aggressively as the Zorí³ do today.

“We had survived for centuries by nurturing the forest, but to survive in the modern market economy, we had to let outsiders come in and chop the mahogany and teak,” says Almir Narayamoga Surui, chief of the Paiter-Surui people. “As the trees fell, the birds went silent, the animals and fish retreated, and our people lost their way.”

But that changed dramatically over the past five years, as most of his people forswore logging and chose instead to earn money from carbon offsets by maintaining the forest and keeping the loggers at bay. Still, some logging continues here as well.

After leaving Sete de Setembro, the trucks briefly pass through the southern tip of the Igarapé Lourdes territory, home to members of the Gavií£o and Arara people who never succumbed to the temptation to chop their trees, and who have a forest that’s thicker and richer than that of their neighbors, but a population that’s financially poorer.

The trucks then pass out into the dusty terrain beyond the indigenous territories, where cattle graze on depleted land and ranchers wonder why their indigenous neighbors refuse to chop their trees for even the Zorí³, the most aggressive loggers among the local indigenous communities, maintain their forest better than do their non-indigenous neighbors. Ultimately, the greatest threat to indigenous lands here and around the world isn’t logging, but the illegal conversion of forest to agriculture. Yet that conversion begins with the construction of access roads like the one connecting the three territories.

Last October, about 80 members of the Gavií£o gathered in their territory, not far from the road traversed by loggers, to weigh their options. Tired of poverty but unwilling to chop their trees, they look with envy on the Paiter-Surui and their ability to earn money by maintaining the forest. Can the same option work for them?

That’s a question that the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazí³nica, or “COICA“) hopes to answer here. Based in Lima, COICA is a federation of indigenous organizations across Latin America. For the past three years, it’s been exploring the creation of a financing mechanism called “Indigenous REDD+” (REDD+ Indígena Amazí³nico, or “RIA”), which aims to blend financing mechanisms like REDD+ (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation, Degradation and other land uses) with existing indigenous practices.

Igarapé Lourdes is one place it aims to pilot the initiative, and if it works it can change the lives of indigenous people across the Amazon.

The Arc of Deforestation

Sixty years ago, the Zorí³, the Paiter-Surui, the Gavií£o and the Arara were isolated people of the Amazon, but today they’re among scores of indigenous communities in the “Arc of Deforestation” a boomerang-shaped band of destruction that sprawls across the southern and eastern edges of the Amazon Rainforest, representing the frontier of what was, just a century ago, a vast and unspoiled forest.

The Arc of Deforestation stretches from the port city of Belém at the mouth of the Amazon to Brazil’s border with Bolivia.

It’s a region of vital importance to the global climate, because indigenous territories of the Amazon hold nearly 30 billion tons of carbon, which would become 110 billion tons of carbon dioxide if it made its way into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change. That’s a real possibility, because more than half of those trees are in danger of being destroyed, according to research by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC), and COICA.

In a paper entitled “Forest Carbon in Amazonia: The Unrecognized Contributions of Indigenous Territories and Protected Natural Areas“, they looked at current threats, like the expansion of access roads, and concluded that roughly one-third of indigenous and protected territories are under “immediate threat” from illegal logging, mining, dams, and agriculture, while an additional fifth are under “near-term” threat.

More than 400 REDD projects around the world are currently protecting a forested area larger than the entire land mass of Malaysia, according to the latest Ecosystem Marketplace State of Forest Carbon Markets Report, and indigenous people across the Amazon have already laid the groundwork for successful REDD projects, although that wasn’t their intent.

Indigenous REDD

Beginning in the 1990s, indigenous people across the Amazon began developing “Life Plans” which are long-term development plans designed to cultivate indigenous economies built on sustainable, traditional practices like the harvesting of Brazil nuts or acai and the creation of handicrafts. All have struggled to get their plans off the ground, but in 2007 the Paiter-Surui achieved liftoff by embracing REDD and becoming, in a sense, modern-day forest rangers.

The Zorí³, however, continued to embrace logging leaving their Life Plan undeveloped while the Gavií£o and Arara began implementing their Life Plans in 2004, only to see them stall for lack of funding.

The quality of Life Plans varies, but most describe land-use and governance programs that are, at the very least, compatible with REDD initiatives.

The Paiter-Surui and the Limits of Project-Based REDD

The Paiter-Surui concluded the world’s first indigenous-led REDD project in June 2013, becoming the first such project to generate offsets by saving endangered rainforest under the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS). Several months later, they sold 120,000 tonnes of carbon offsets to Natura Cosméticos, a Brazilian cosmetics giant.

But what worked for the Paiter Surui in Mato Grosso might not work for all indigenous territories facing dire threats from deforestation. The Gavií£o and Arara of Igarapé Lourdes have been much better stewards of their forests than either the Zoro or the Paiter-Surui, and while all four communities including the Zorí³ have preserved their forests better than the non-indigenous settlers have, the people of Igarapé Lourdes have done the best job of all. Yet, ironically, this fact may keep them from fully utilizing REDD finance. The situation is something of a Catch 22: to earn carbon offsets to protect forests and fund the implementation of their Life Plan, the trees of today must face measurable, imminent destruction.

The Paiter Surui REDD project became a reality because they were able to demonstrate this risk of imminent deforestation and thus reduced carbon storage under a business-as-usual scenario called a “baseline”.

- To learn more about the Paiter-Surui and their Forest Carbon Project, see “Almir Surui: Perseverance Under Pressure“.

So while a REDD project can help some indigenous peoples improve their stewardship of the land, it may not be applicable to the peoples of Igarapé Lourdes and certainly not the “uncontacted” indigenous peoples inhabiting wild, remote areas of the Brazilian Amazon. It is believed that nearly 70 such indigenous groups continue to live in isolation in the Brazilian Amazon alone, according to a2007 estimate from Brazil’s National Indian Foundation (Funai), higher than past estimates of about 40 groups. What’s clear is that conflicts with miners, ranchers, farmers and loggers will increasingly force such groups to confront the world at large, and in particular, incursions for resource extraction.

In the same year of the above estimate, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renoví¡veis, IBAMA) forced hundreds of illegal settlers from the Uru Eu Wau Wau indigenous territory in Rondí´nia where uncontacted groups are believed to reside.

Dealing With a Funding Dilemma

If it’s not possible to emulate the Pater-Surui, how do people like the Gavií£o and Arara resist logging and other short-term resource extraction pressures that are sure to increase in time? And what of the indigenous peoples who remain uncontacted, living in remote areas?

The challenges ahead to protecting the forests of such unexplored indigenous areas are immense: across the Brazilian Amazon today, about 15 percent of indigenous territories have still not been even been defined with boundaries or officially demarcated.

“All across the Amazon, we have indigenous people crying out for help to defend the forest,” said COICA head Juan-Carlos Jintiac at recent year-end climate talks in Lima, Peru. “But because they had no deforestation, they had no access to REDD finance.”

In light of the importance of indigenous territories to the planet’s carbon stocks and the current threats to such a resource, how can these many good stewards of the forest be rewarded for what they are doing? More precisely, how to fund the life plans that are so central to developing an enduring sustainable economy?

Where to Get the Money?

One alternative path forward is for states to seek REDD finance for reducing deforestation across their entire jurisdiction, and then distributing the funding in-state as they see fit. The tiny state of Acre, to the west, of Rondí´nia, has pioneered this “jurisdictional” approach to REDD and is rewarding indigenous peoples with funds for good forest stewardship. The money comes into the state as REDD finance, but is distributed internally for activities that conserve water and protect endangered species.

- To learn more about Acre’s jurisdictional REDD program, read “Acre and Goliath: One Brazilian State Struggles To End Deforestation“.

The premise is this: good forest management and carbon sequestration go hand-in-hand, but payments for one ecosystem service will result in benefits to another and for indigenous people, there is a chance to resurrect their traditional practices built on sustainable resource extraction, eco-tourism, and handicrafts.

In 2013, the German development bank KfW committed to financing the reduction of 8 million tons of emission reductions from Acre in a four-year, $40-million agreement the first ever payment for emissions reductions at the jurisdictional level. Such payments are to flow from the state government to indigenous groups and communities based on a variety of activities under Acre’s State System of Incentives for Environmental Services (known as “SISA”).

Deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest

Beyond REDD, there are other potential sources of funding. One could come from municipal and state levels via the federal ICMS Ecolí³gico (Ecological Tax on Goods and Services / Imposto sobre Circulaçí£o de Mercadorias e Serviços Ecolí³gico) program, which allows local governments to access a refunded portion of the value added tax collected in their states, based on the amount of forest cover and water resources in their jurisdiction. To date at least 24 Brazilian states have passed laws or are debating legislation related to creating a green value-added tax.

Other Shades of REDD

Acre is both an innovator and outlier the jurisdictional REDD solution pioneered there is not a fit for many other states in the Brazilian Amazon, where much larger populations and vastly more diverse deforestation pressures continue to converge. That said, some form of jurisdictional REDD administered from the state level is moving forward across much of the Brazilian Amazon.

At least four other Brazilian states have embarked on statewide REDD programs, and each is unique: Mato Grosso, which destroyed its forests at a devastating rate to make way for soybean production, has slashed its rates 90% and created the country’s most advanced regime for keeping track of REDD payments. Meanwhile deforestation is picking up in states that have historically had little deforestation, like Amapa.

Consider Rondí´nia itself, home to the Zoro, the Surui, and the indigenous peoples of the Igarapé Lourdes territory, where discussions to create a state-wide jurisdictional REDD system, with state and municipal government support, have already started.

As COICA and the people of Igarapé Lourdes further explore the potential for Indigenous REDD+ (RIA), jurisdictional efforts operating outside carbon markets may prove to be the most viable funding source.

Next Week: Life Plans: Foundation or Fools’ Gold?

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.