The UK Finds “Net Gain” Might be Cheaper Than “No Net Loss”

In the United States, species and wetland markets are built on the concept of “no net loss,” which often requires extensive surveying to determine exact impacts. In the United Kingdom, a new bank is experimenting with guaranteeing a net gain – in part because it’s the right thing to do, but also because it may be more cost effective.

23 October 2019 | When British Ecologist David Hill launched the UK’s Environment Bank in 2009, he followed US precedent and built it on the premise of ensuring “no net loss” of habitat for infrastructure and housing projects that impact protected areas. He soon, however, started pushing for policies that go beyond “no net loss” and instead deliver a “net gain” of habitat whenever offsetting is involved.

“It’s the right thing to do,” says Hill, “but it also makes economic sense, because off-site mitigation is orders of magnitude less expensive than on-site mitigation is.”

From Local Experiments to National Law

When Hill launched the Environment Bank in 2009, offsets had no status under UK law, but they were recognized in two key European Union directives – one for Birds and one for Habitats – as a tool for meeting conservation objectives related to the Natura 2000 protected areas program, and Germany had utilized offsetting since 1976.

The UK began piloting offsets for regulatory purposes in 2011, and the Government’s Ecosystem Markets Taskforce recommended mandating them in 2013, but a blatantly distortive campaign by provocateurs like George Monbiot of the Guardian delayed implementation. Hill responded by growing the bank on a county-by-county basis, always emphasizing the concept of “net gain” and forging agreements with local planning authorities to create offsets that are recognized under existing planning policies and meet the permitting requirements of local authorities. Once the regulatory requirements were clear, the bank would enter into binding agreements with both developers looking to mitigate for biodiversity impacts and land owners looking to sell offsets by placing conservation easements on their land.

In March of this year, his perseverance – and that of dozens of other ecologists – paid off when the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced that the net gain provisions would become official UK policy.

The Business Plan

As its US counterparts do, the company identifies farmland or other areas that are suitable for habitat creation and enhancement in regions of accelerating development and negotiates conservation easements on the land – in this case, of 30 years or longer. It aims to make a profit by charging up-front consultation fees for identifying biodiversity risks and then transaction fees and brokerage for delivering the mitigation, as required.

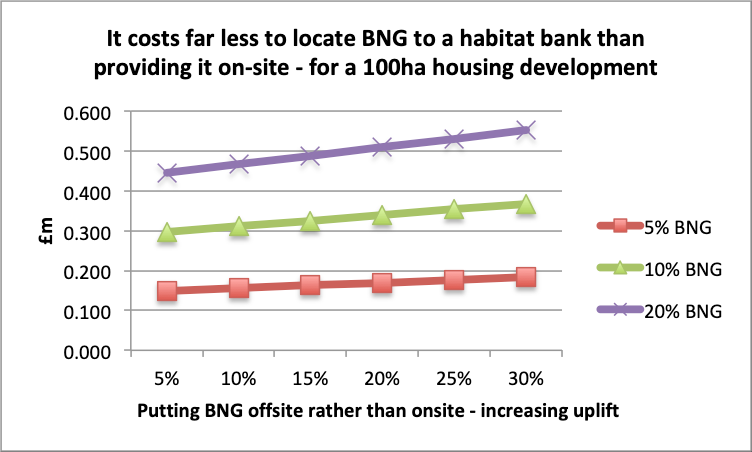

According to a business analysis that Hill created, the cost of developing habitat off-site on degraded land is at least 1/30th that of developing habitat on-site, with the bulk of the savings coming by eliminating the cost of using land purchased at development rates for habitat creation, eliminating the cost of losing development revenue (because the land taken up to deliver biodiversity net gain cannot be used for the development, and eliminating the costs of 30 years of management and monitoring of the biodiversity within the development site).

The analysis examined the cost of on-site mitigation for a 100-hectare housing development with various ratios of developable area and public open space, ranging from 80 developable/20 open to 60 developable/40 open. While the cost per square meter of ecological construction was fairly low, the cost of lost income from undevelopable land was significant. Using the 80/20 scenario and assuming typical rates of various habitat cover common in the United Kingdom, he showed that developers achieving the required 10 percent net gain off-site could build 2800 housing units, but a developer delivering just 10 percent of that mitigation on-site would build 343 fewer units, and a developer delivering just 20 percent of the mitigation on-site would build 686 fewer units.

Biodiversity Metrics and Calculators

In 2012, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) introduced a metric for measuring the biodiversity losses and gains that result from development projects, and that metric was then upgraded through a technical review process into the Defra Metric 2.0, which can take account of linear features and other requirements.

The Environment Bank was one of a number of experts who contributed to the upgrade, which is expected next year, but it also worked with local planning agencies to create the Environment Bank Biodiversity Impact Calculator, which is available for free and includes local priorities and circumstances. The Environment Bank Calculator builds on the Defra Metric and can be used to estimate a site’s biodiversity impacts and compensation needs. Those using the Environment Bank calculator then approach them to find an offset or habitat bank solution in order for the development to be policy compliant and deliver biodiversity net gain.

The Role of the Bank

Because everyone involved in biodiversity mitigation uses the same metric, there is little disagreement on impacts and how to apply the mitigation hierarchy (see “Mitigation Banking”). Once net gain becomes a mandatory requirement of the planning system, this will create a standard under which the development sector can operate. Hill believes the level playing field and certainty provided will also stimulate significant investment into offsite habitat creation, enhancement and long-term management.

The Environment Bank, in other words, presents itself as the leading option for dealing with unavoidable habitat loss, and offers a vehicle for dealing with it – a necessary step for getting a permit. The metric ensures that losses and gains are accounted for in the same way, rather than in a subjective approach. Hill emphasizes that the real value of the Environment Bank is that it provides offsite solutions which are easier for developers, far less costly, and deliver far greater benefits for nature conservation than trying to place ‘biodiversity’ within the development site. It does this by facilitating the creation and long-term management of large areas of land specifically for nature.

Permanence and Uncertainty

Developers acknowledge that current metrics have an inherent amount of uncertainty, but in a theme that emerges repeatedly in our interviews, the project reduces cost by sacrificing precision, yet it increases ecological integrity by adding in buffers that more than offset any uncertainty.

Specifically, companies purchasing offsets are required to compensate by applying multipliers of between 4:1 and 8:1, which is significantly higher than the uncertainty. The key attraction to developers is that they can use the Environment Bank model with ease and don’t get burdened with a long-term liability for habitat within their development site, which almost always gets changed by occupants through recreational use, lack of management or cutting in the interests of tidiness.

Although the contracts only last 30 years, the property could then be protected by law through the application of voluntary agreements on the land. But by choosing the right landowner with an interest in wildlife, it is considered that once established these sites will remain as part of the national infrastructure for nature, in perpetuity.

Permanence is not assured, but land can become recognized as habitat and would then need permission to develop, and owners could create a “conservation covenant” that could, for example, provide tax-free status. David Hill is advocating the use of Conservation Property Relief (CPR) on these areas. Much in the same way that farmers get tax relief through Agricultural Property Relief (APR), why not incentivize those who do good for conservation in the same way, or indeed replace APR with CPR to incentivize more conservation creation and management.

The Economics of Saving Newts

Hill is putting the practices to work through a company called the NatureSpace Partnership. It uses off-site habitat creation for the conservation of great-crested newts, a species given the highest level of protection under EU law. Joining a NatureSpace scheme eliminates the cost to the developer of having to survey for newts and the huge cost of mitigating for them if newts are found. NatureSpace provides the solution to de-risk the development industry and provide far better population-based conservation for newts.

The bank secured funding of £1.5 million and proactively paid land-owners for easements and built ponds, then began marketing with the objective of expanding the initiative from one region of the UK to several more, using a ‘District Licensing’ approach regulated by Government.

Cutting the Cost of Surveying

One of NatureSpace’s strategies it to reduce the cost of surveying newts. The company used the investment to survey a stratified set of ponds in the South Midlands region of England using environmental DNA, and used the survey data to model newt distribution and abundance˘. They divided the South Midlands into five color-coded impact risk zones: black no-go zones where the newt is protected and no development should take place, red where the newt is likely plentiful, amber where newts are likely present but at lower concentrations, green where the newt may or may not be present, and white where it is probably not present.

This reduces costs because the development industry traditionally surveyed ponds on a site-by-site basis, and if newts were found had to apply separately for a specific license, and follow a detailed and problematic methodology to determine presence, which very often led to delays or prevented developers being able to get on with the development for many months, all creating great cost to the industry. Individual mitigation schemes were found by the government to be only 3 percent successful and to present a serious cost burden to developers. NatureSpace, using the District Licensing approach, made it possible for developers to first search regionally to determine risk and to pay for a pre-application assessment. Depending on where the development is located (black, red, amber, green or white zones) the developer pays a second fee on the permitting of their development in order for new newt habitat ponds to be created in strategically located areas agreed with the permitting planning authority.

Landscape-Level Surveys

In traditional mitigation, the cost of conducting a site-specific survey can be up to seven times the cost of carrying out the mitigation itself, and developers often incur this expense only to find that the concentration of newts is too high for development. Such areas can now be screened out early and the best areas become unsuitable for development. But the NatureSpace model has eliminated the need for site-specific surveys to be undertaken at the development level by creating regional surveys that identify concentrations of habitat across entire landscapes, modeling the data to produce these ‘heat maps’ of newt distribution.

To date the take up by developers has been very high in those planning authorities engaged by NatureSpace as it saves them time and money and is better for newt conservation at a population level.

Battling Entrenched Interests

The greatest challenge is in ensuring environmental consultants recommend the new District Licensing approach to developers since the consultant industry makes a significant income from conducting site-specific surveys, carrying out lengthy translocation exercises including the erection of barrier fencing, and designing and building newt habitat next to or within the development in some way. Consultants can, however, now play a critical role in ensuring that their developer clients are made aware of the new licencing model and can work with Environment Bank to monitor the large-scale habitat creation schemes that they are facilitating. These schemes are already proving to be more successful than the ‘old’ licensing method because more habitat is created and newt populations are better protected because of the expansion of range at significant spatial scale.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.