REDD Dawn: The 60-Year Evolution Of Forest Carbon

This story is excerpted from the upcoming book “Carbon Cowboys and REDD Indigenes”.

21 September 2018 | The Paris Climate Agreement aims to keep global temperatures from rising another 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Farenheit), and one way it aims to achieve that is by funneling money into forest conservation and sustainable farming through a mechanism known as REDD+, which stands for “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, plus other land uses”.

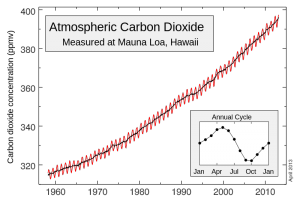

But while REDD+ came of age in the Paris Agreement, it was born thirty years ago, in 1988 – not so much to save the planet as to help poor farmers in Guatemala manage their land more sustainably – and its germination began three decades before that, in 1958, at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. That’s where the late American scientist Charles Keeling started measuring the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, an exercise that eventually yielded the “Keeling Curve”: a diagonal line that zigzags upwards as CO2 levels increase year-to-year.

2. Source: Global Warming Art Project

The Keeling Curve: This is your planet on CO2. Source: Global Warming Art Project.

The upward slant continues to this day, while the zigzags reflect the rhythm of farms and forests in the Northern Hemisphere coming alive in summer, when they sponge up CO2, and falling dormant in the winter. If this natural rythm had such a pronounced effect on the atmosphere, scientists began to wonder, what impact does rampant deforestation have? How much of our greenhouse gasses come from industrial emissions, and how much form chopping trees?

Scientists had known about the greenhouse effect since the early 1900s, when Swedish scientist Svante August Arrhenius dubbed it the “hot-house” effect, but Keeling’s curve showed that CO2 levels were rising faster than most believed. As the curve continued to climb over the ensuing decades, so did interest in climate change.

Trees and Climate Change: An Early Defense

By the early 1970s, scientists were beginning to see climate change as a very real but distant threat – one that would eventually force us to completely restructure our industrial economy. Physicist Freeman Dyson was one of those who decided to get ahead of the challenge by looking for workable solutions.

“Suppose that, with the rising level of CO2, we run into an acute ecological disaster,” he wrote in a 1977 article entitled “Can We Control the Carbon Dioxide in the Atmosphere?“, published in the journal Energy. “Would it then be possible for us to halt or reverse the rise in CO2 within a few years by means less drastic than the shutdown of industrial civilization?”

His conclusion: yes, it would be possible to slow climate change by planting trees – but not as a permanent solution. Instead, he saw trees as a short-term, stopgap measure that would slow the process long enough for technology to catch up.

“The long-term response, if such a catastrophe becomes imminent, must be to stop burning fossil fuels and convert our industry to renewable photosynthetic fuels, nuclear fuels, geothermal heat and direct solar-energy conversion,” he continued. “But a world-wide shift from fossil to non-fossil fuels could not be carried out in a few years… An emergency plant-growing program would provide the necessary short-term response to hold the CO2 at bay while the shift away from fossil fuels is being implemented.”

Trees and Sustainable Agriculture

Meanwhile, in 1974, humanitarian organization CARE had launched a program called Mi Cuenca (My Watershed) to help Guatemalan farmers save their topsoil – in part by planting rows of trees on steep farmland to capture runoff and create natural terraces. The project soon became an unqualified success, and farmers across the region were clamoring to join, but by 1988 CARE was running out of money, and the project was on its last leg.

That same year, the United Nations launched the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to explore the science of global warming, while an energy executive named Roger Sant started looking to expand his company’s output – preferably by building wind farms. A proponent of green energy in the Carter Administration, Sant had co-founded a company called Applied Energy Services (AES), in part with the objective of making green energy work.

Rural Development and Reduced Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Wind-farm technology, however, wasn’t what it is today, so Sant asked the World Resources Institute (WRI) if there was a way to offset his emissions by reducing them somewhere else – a radical concept at the time. WRI picked up Dyson’s idea – which other scientists had since moved forward – and suggested he plant trees across the United States. That quest found its way to Paul Faeth, an agricultural engineer with the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), which was in the process of merging into WRI.

Faeth knew of Mi Cuenca’s plight, and he proposed killing two birds with one stone: by planting trees in Guatemala, he said, AES could help both the environment and the rural poor.

Intrigued, AES began working with WRI to explore the science of carbon accounting – science that had, ironically, been perfected by timber companies to estimate the amount of wood in a forest. It was a simple but labor-intensive process that involved measuring trees at chest-height and then applying “allometric equations” based on the trees’ species and circumference to see how much wood they contained. From there, it was simple math to extrapolate the amount of carbon: basically, divide the wood by two.

But there was more to it than just the carbon in the newly-planted trees.

Deforestation and Climate Change

Researchers at the time were estimating that deforestation contributed about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions – estimates that have since been confirmed by the IPCC. That meant you could reduce greenhouse gas emissions faster by saving endangered forests than by planting new trees, which would need decades to get big enough to matter. Plus, living forests provide habitat for endangered species and deliver “ecosystem services” such as water filtration and climate control. On top of that, saving forests seemed inexpensive.

WRI had just hired a policy analyst named Mark Trexler, who pointed out that any trees they planted on the slopes would also save endangered forest further up, because farmers wouldn’t have to keep abandoning their land for greener pastures. That, he argued, was more important from a carbon perspective than planting trees – especially if many of the newly-planted trees ended up being cut down to supply farmers’ immediate needs. He proposed focusing their attention on saving the trees

In the end, AES decided to spend $2 million to save and expand Mi Cuenca to offset 2 million tons of its own internal CO2 emissions. CARE re-named the project “Mi Bosque” (My Forest), and today their experiment is considered by some to be the world’s first REDD project. Although a later analysis found it drastically over-estimated the amount of carbon that was kept out of the atmosphere, it sparked the decade of experimentation that led to the creation of today’s rigorous carbon standards.

Climate Talks Begin

The project caught the eye of The Nature Conservancy, and pilot projects started proliferating across Latin America. The term “REDD” wouldn’t enter the vernacular for another 15 years, but NGOs began developing structured, methodological approaches to “Avoided Deforestation” (AD), which became a hot topic at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, as well as at the First Conference of the Parties (COP 1) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Berlin in 1995.

As climate talks progressed, analysts like Trexler and ecologists like Tia Nelson of The Nature Conservancy argued for the inclusion of REDD in the UNFCCC framework as a critical means of immediately dampening the rise in greenhouse gases.

On the REDD front, proposals ranged from “project-based” frameworks like Mi Bosque to “national baseline frameworks” using a country’s historic rate of deforestation as a performance baseline and then offering payments for beating it.

Politics and Science: the Great Divide

The proposals, unfortunately, found little traction – for a variety of reasons. To begin with, few climate negotiators had a forestry background, so the science was lost on them. Furthermore, “offsetting” had become equated with “incentivizing industrial reductions”, and most environmental organizations were horrified by the idea of cheap offsets, which they feared would flood the market and remove the incentive to change industrial practices. Finally, developing countries – still mindful of their recent colonial past – feared that REDD would cost them control of their forests. On top of all that, no one really agreed on how best to determine which forest was in danger and which was not.

As a result, when the Kyoto Protocol emerged from COP 3 in Kyoto, Japan in 1997, REDD was off the UN table and relegated to voluntary markets, where it continued to evolve at the pilot scale under real-world conditions.

Voluntary Carbon Markets

Over the next 15 years, standard-setting bodies like the Verified Carbon Standard and the American Carbon Registry emerged to provide ways of determining which forest was endangered and which procedures can be used to save it. At the same time, the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance emerged to ensure indigenous rights, and forest communities that embraced REDD found themselves able to earn income from their stewardship of the land.

Within the UNFCCC, however, REDD remained on ice until 2005. That’s when Papua New Guinea wrangled it back onto the agenda at Climate Talks in Montreal (COP 11). In 2010, REDD was the sole bright spot in the otherwise dismal Copenhagen Accord. By 2011, governments around the world were harvesting the lessons of voluntary REDD pilot project developers and offset buyers to launch larger-scale regional REDD programs that accounted for avoided deforestation at the “jurisdictional” scale but still allowed early pilot projects to generate emissions reductions and earn offsets and revenue (i.e. “nest”) within their borders. The UNFCCC and World Bank, however, steered clear of anything involving offsets and drifted toward purely jurisdictional approaches that left individual projects in limbo. (If that seems like a lot to swallow, keep reading the articles that follow.)

Then, at the 2013 climate talks in Warsaw, the UNFCCC finally agreed on a REDD Rulebookfor jurisdictional REDD. Technically, it’s not a book, but a collection of seven decisions that provide guidance on how countries can harvest available data to earn REDD income. The Rulebook’s provisions for program development are significantly less rigorous than the standards imposed on voluntary projects, but the payments into jurisdictional programs aren’t offsets – meaning countries can’t claim to have reduced their own carbon footprint. Instead, jurisdictional programs are increasingly seen as “payments for performance” that could slow deforestation by supporting sustainable agriculture – while at the same time creating a framework within which more rigorous individual projects can address specific local challenges.

Please see our Reprint Guidelines for details on republishing our articles.